A Career of Choice

Or, why you ought to consider taking up a skilled practice and pushing the kids in your life towards a career in the trades. There is a lot to say. Feel free to hop between sections!

Well hello! If this is the first newsletter you’re receiving from me: thank you so much for subscribing. I hope you won’t be sorely disappointed!

This is a follow-up to my previous post in which I discuss how plumbing was an unexpected career for me and tell the story of how I ended up being a good old fashioned wrench-turner. I’d encourage you to go back and read it if you haven’t, then return here and continue.

What I’ve written below is a longer piece than I had intended, but there’s a lot to say on the topic of why someone might choose a career in the skilled trades. In my opinion, the opening, the “Becoming” sections, and the end are my most important points if you’d like to abbreviate the reading.

Go on. Ask me. Ask me to gripe about something in the trades, to really indulge in some self-gratifying bellyaching. I dare ya.

…

…Thank you.

I choose our promotion. Trades promotion sucks big time. It’s so incredibly one-sided and I can sum it up for you as follows:

There’s always need for laborers.

You’ll make great money.

There, I just saved you from every career fair in your local area and the vast majority of blog posts trying to get people interested in being an electrician or a plumber or a welder or a carpenter.

“That seems…not wrong, Nate.”

Well, like, listen. It’s not for nothing. There is a need as the trades are hemorrhaging laborers to retirement, death, and the decades-long college degree PR campaign. Money is a concern for most people, especially as the US economy continues to fight the downward pull of fiscal gravity, and finding a career that can consistently make you a livable wage is like finding the actual Golden Goose.

The problem with these talking points aren’t that they’re wrong. In fact they’re quite right. The problem is that they don’t come close to capturing why a career in the trades can be put forward as a career of choice, an esteemed vocational path. College degrees have been made sexy, and the trades decidedly unsexy, through years and years of imaginative formation by our culture. Manual labor has become nonerotic not just by comparison but by default. Given the choice between taking up wrenches or starving, many would — and do! — choose an empty belly.

If the blue collar world to which I happily belong stands any chance of recruiting folks into its ranks, the way we talk about the trades has to overcome a problematic, near-erotic desire, a desire whose siren song lyrics have been so forcefully chiseled into the stone tablets of our collective psyche that generations have chanted it while uniformly marching directly into financial and myriad other ruins: follow your passion.

It’s a trap. A psyop. A delicious bit of disastrous advice that has left entire fleets obliterated against the rocks. But like broken records, we keep playing it through our various cultural phonographs like it’s the only thing we know how to say. Frankly, it just might be.

Another facet of this — one which I have no way to discuss in any real depth or make any systemic-level recommendations, and even if I could, I don’t think I would as I believe this must be handled locally and discretely — is a corollary of the above: we must tutor our children’s desires as best as we’re able. Acquiring taste is a long process of refinement and training one’s powers of attentiveness and discernment. This is our role as parents. This is education. Shaping our kids’ desires so they are amenable to, inclined toward, what is actually good in this life means there will be less to overcome when suggesting it. What is good often appears grossly undesirable. Do with that what you will, but I think it’s a necessary consideration.

Lastly, and something I see at the ground-level: if we continually promote the trades as “a great way to make money” to the exclusion of all the other things that could be said about them, we might increase the total number of people doing the work, sure, but they will largely be money-oriented people. And homeowners famously love having a revenue-hungry technician in their house.

Okay. Griping is over and now we take a turn towards the Much Better Way that I hope to keep pumping through our societal phonograph horns.

At the end of my last post I mentioned how schoolkids will always ask me about the money, but I wave that question off to talk about other stuff first. Here’s some of that other, much cooler, much better stuff.

The Statistics

Okay, not this one. Younger kids don’t care about the stats, so this doesn’t come up as much but it’s important to know what kind of competition one might be up against when considering entering (or pushing an unsuspecting child into) this particular talent pool of the American workforce. TL;DR for those that want to skip to the next (and far more interesting) sections, the numbers tell us that the water’s fine and any blue collar employer that doesn’t have a “help needed” sign out front is lying to themselves.

On Twitter the other day I quipped:

This was an arbitrary group of professions and there are plenty that could be added to them to inflate the number, but the point remains that the total is overwhelming in its smallness. The problem is not that the jobs aren’t available; quite the opposite. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics there are ~10.1 million total available jobs and ~6 million people out of work, meaning if every available position in the US job market were filled by every person needing one, there would still be ~4 million jobs left to fill. About 3 million of those 10.1 million jobs are in the skilled trades, so don’t all 6 million of you rush in on 'em at once!

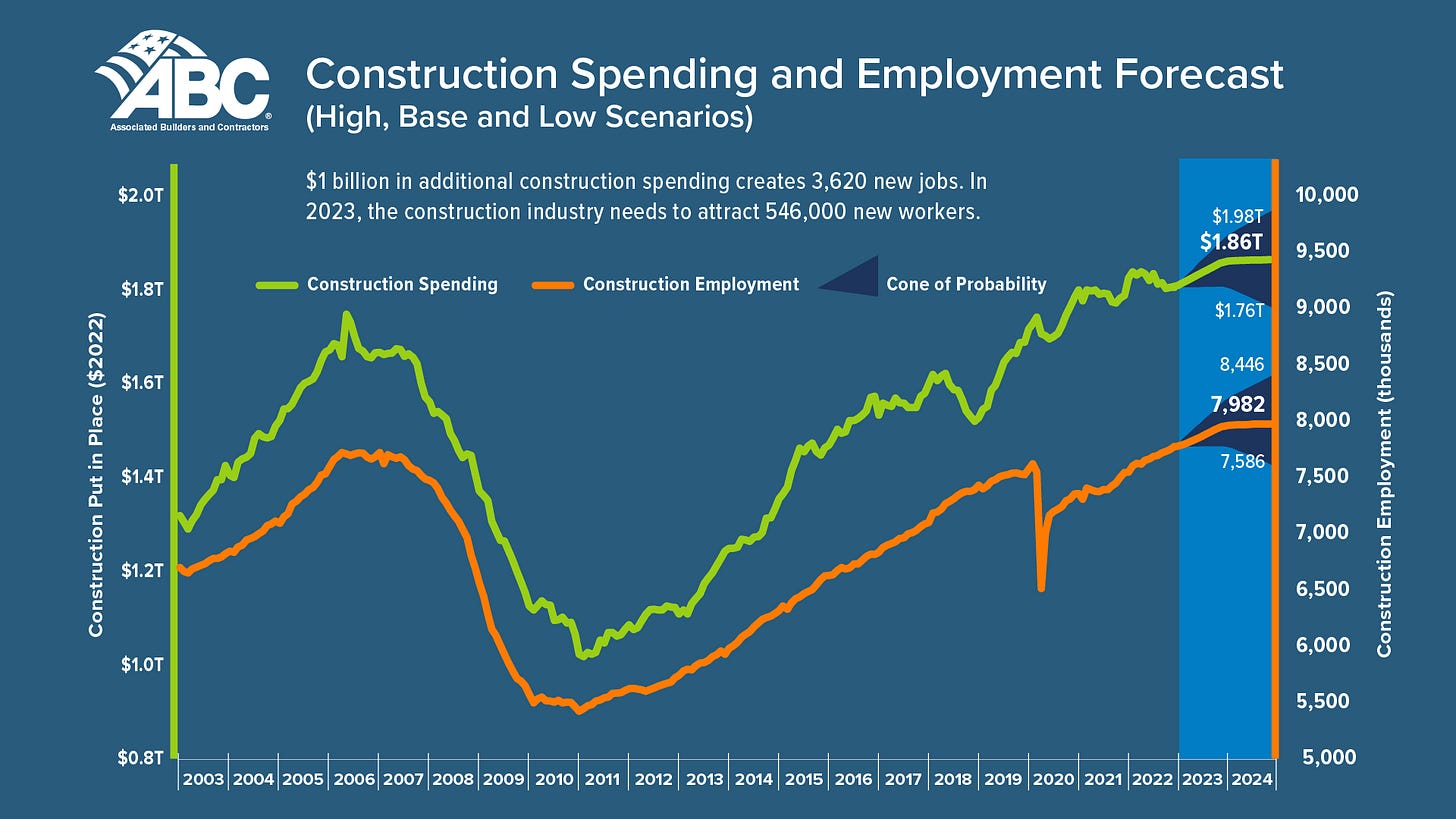

This graphic from the Associated Builders and Contractors shows us that in the construction industry alone, they’ll need to hire 546,000 new workers by the end of 2023. If I were a betting man, I’d bet that right now at halfway through the year, the industry probably isn’t halfway through that number.

US Manufacturing alone accounts for 693,000 job openings. The country needs 48,600 plumbers, 79,900 electricians, 47,600 welders, 73,300 mechanics, 44,100 machinists, 93,800 barbers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists, 85,600 farmers and ranchers, and the list goes on and on.

To put this in perspective, let’s take the US state I call my home, Georgia, and my sector of the plumbing industry, residential service and repair. The BLS’s Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics system tells me that there are ~7,720 employed plumbers (which doesn’t match with the total number of active plumbing licenses in the state, but I’ll save licensure for another essay). The Census Bureau estimates that the Georgia state population is 10,912,876. That’s one plumber for every 1,414 people, IF every one of the 7,720 plumbers were in the residential service and repair industry. (Hint: they’re not.) These plumbers are split between residential new construction, commercial new construction, industrial new construction; residential, commercial, and industrial service and repair; facilities management; public infrastructure; code enforcement — so the ratio of plumbers to people that need plumbers is astronomical. Worth noting is that not each of those 10.9 million people are homeowning adults, so maybe the ratio isn’t quite as dismal, but there’s no getting around the fact that there are simply not enough residential service plumbers to keep up with the volume of 30-50 year old homes in the Atlanta metro area that are springing pinhole leaks faster than you can say “catastrophic failure.”

This is only a peek at the state of plumbing in America, which we can take as an indicator of the trades more broadly.

In sum, job availability isn’t the problem — I doubt there’s a person left in our country that doesn’t know these jobs are ready for the taking even if they aren’t familiar with the numerically bleak picture. Job desirability is the problem, which brings me back to my point that how we talk about these jobs is more important than the fact that they are there waiting to be filled. They aren’t gonna get filled if no one wants to fill them, and the material world around us is literally falling to pieces while we wait for that to happen. So why might someone want to pursue this plenteous labor if not for the availability and money to be made doing it?

Becoming Whole

At the end of the day, people desire far more than the abstracted, embodied value we know as “money.” (The only people that might really want money in and of itself are those who find themselves among that adorable flock of odd ducks, the numismatists. Coin collectors. But that’s it.) Right or wrong, everyone is after money for what they think it can purchase for them: sustenance, comfort, shelter, utilities, power, status, fame, legacy, contentedness, love.

Happiness.

People want to buy happiness. Annoyingly, it can’t be bought readymade. It is hard-won through long years of cultivating one’s inner life, the realm of thought, emotion, intention, and will. And what I’d like to suggest is that as far as careers go, manual labor, in particular those manual labor jobs that rely on skilled activities, is an excellent choice for disciplining one’s interior world while simultaneously working on the material world around them, and, in the end, winning their happiness.

It’s career day and I’m standing in front of a carefully manicured plywood wall with clear PVC drain lines zig-zagging back and forth across it. I ask the kids gathered before me, “What are some of the invisible things about you that you think make you a good person?”

“I’m kind.” “I’m smart.” “I’m careful.” “I’m patient.” “I’m creative.”

The answers are good ones. “And what are some of the things that you do with your bodies that you think make you a good person?”

“I help my parents with the chores.” “I build robots with my brother.” “I rake up leaves in my neighbor’s yard.” “I sew baby clothes for new mommies with gramma.”

Their actions embody these inner virtues they’ve listed off. “When you do these things, how do they make you feel?”

“Good!”

Often, the kids don’t seem to notice that the invisible bits of them and their outer works are connected to one another, so I’ll point it out.

Curiously, this is true for most of us anymore. Our identities and our various faculties have become so splintered, so atomized, so disintegrated that we’ve lost an awareness that our inner and outer worlds are mutually dependent and formative, one on the other. And the means by which this formation is mediated? Our bodies. Let me give you a personal example.

When I replace the tank-to-bowl kit on a finnicky old toilet and I can’t get the various gaskets to seal just right after three or four different attempts, I don’t just have a leak. I have an affective movement. A shock of anger that manifests as a terse chuckle escapes through clenched-teeth. A bead of sweat rolls into my beard. This should be so easy, what the **** is my problem? My thoughts are at a rolling boil that matches the feelings in my chest as I narrow my attention in an attempt to notice what I’ve clearly missed. My emotions distract my intellectual faculties from doing their job, so I engage in some deep diaphragmic breathing and the Jesus Prayer to regain control of myself and try again. My hands reach forward to remove the bolts (again) so I can lift the tank up from the bowl (again) and check (again) for maybe a hairline fracture or some other defect in the porcelain that might prevent it from sealing.

“You’ve got to be kidding me.” A flash of orange is sitting there, suddenly plain as day in front of me. You see, I’m working on a Gerber toilet but I’ve been trying to use a Fluidmaster tank gasket, known by its carroty hue. They’ll work on ninety-nine toilets, but a Gerber ain’t one. Gerber toilets require a much thicker gasket to make up the gap between the tank and the bowl. I assumed it was a defect in the toilet that was the issue, when it was really my own mistake. My emotions and intellect have been tutored; my soul has been trained in the virtue of humility; my eyes and hands are further instructed in key sensory-action circuits; my spirit learned afresh reliance on God.

I now get to reconnect the supply line, fill the tank, and drink in the satisfying sound of a toilet flushing just as it ought to. Water where I want it and not where I don’t. I guess I’m really a plumber after all.

In a single activity, the world outside of me — a customer’s leaky toilet — and the world inside of me — my thoughts and feelings and morals — were ordered. Mastery of the toilet and mastery of myself were completely tied up in one another.

Skilled activities that require the use of our bodies are a rare occasion for re-integrating all of our fragmented, disparate parts, recruiting as best as we’re able and focusing all of our faculties on the task at hand. In a culture that seems hellbent on treating us as brains in a jar on the one hand or a vivified meat sack on the other, skilled labor appears to defy and resist the fractal disintegration we see at the biggest and smallest discernable scales.

Only whole people can be happy, and if that’s what people are really after, then a manual labor career is a great way of becoming whole.

Becoming Handy

Before plumbing, I couldn’t do diddly. Tools all blurred into each other, an amorphous mass of plastic and metal with no apparent difference in form or application. I could hammer a nail into the wall for hanging pictures, but I was of absolutely no use in any other way.

Since plumbing, I’ve learned: plumbing (duh), which includes water distribution systems, exhaust venting, sewer systems, sewer venting, and gas distribution systems; some framing; low voltage electrical; a bit of HVAC; home insulation practices; how to dig a hole and various soil types; how to cut drywall and then replace and mud it; how to cut, remove, and patch concrete; and if I thought harder I could probably identify some more. Specializing in one trade, particularly in a construction trade, requires at least cursory knowledge of the trades with which it interacts and moves through (e.g. my plumbing runs through the framer’s studs and joists, so I have to understand structural load and how much of a stud or joist I can cut; sewers run under concrete, etc.).

This translates practically into saving money in a lot of cases: $75 in parts, some YouTube videos, and a couple hours of earnest struggle could save me a $500+ invoice from a service technician.

An underappreciated facet of learning a skill is its transferability to other tasks. When you learn how to properly use a Phillip’s head screwdriver in, say, a woodworking project, it becomes very easy to apply your knowledge of a screwdriver under a truck hood (acknowledging, of course, that there’s a literal truckload of other things you have to know beyond a screwdriver, but it gets you in that direction). This extends beyond tools to more abstract concepts like physics or chemistry, or more concrete tasks like manipulating sheet metal or running condensate hose. By learning and understanding well the use of these particular tools or concepts or tasks, you open up to yourself a world of potential work that is yours by analogy.

So not only do I a) do work that is in demand and helps train and form my interior world such that I am made whole and learn to be happy in this life, I b) also do work that gives me the skills to have a bit of mastery over my own home and environment.

Becoming Dependable

Becoming handy sends ripples not only through the fabric of the material world, but also through the social and relational realities around me.

While it is true that people are inherently valuable and ought to be loved on the basis of their share in the imago Dei, it is also true that not every individual can be depended on when things need doing. I think that we all have a sense of this. We want to contribute. We want to feel deep in ourselves that we are worthy of the value other place on us, which, to a larger degree than is popular to admit these days, requires the validation of my family and friends and neighbors. The refrain of my generation was some variation of, “I want to have an impact” or “I want to leave a legacy,” which is, no doubt, a good desire, but nobody seemed to know how they would go about doing either one.

Becoming handy has given me a specific, tangible means by which I can contribute directly to the lives of the people around me. These skills that I’ve picked up and the virtues that are trained by their dutiful practice are now deployed in service to my friends and neighbors when they’re in need. My community can depend on me. It’s precisely in this realization, as I bump up against the needs of others and satisfy them, that I find the outline of myself.

I was texting back and forth with a buddy the other day, with whom I share a love for the Disney parks, and he asked me, “Why not be a plumber at Disney?” Early on that was a consideration, and for a while I thought I’d try to make my way back into park operations as a plumber. But I’ve become convinced that doing this work (and training people to do this work) in people’s homes is more important than plying it in a theme park (even if it’s one I and my family really enjoy). To plumb for the Mouse — and trust me, he needs plumbers bad — would be to risk losing the core of what I’m doing. People’s homes are a central, formative space, and the relationship between one’s identity and one’s home are a close one. I prefer to put my skills in service to that relationship.

Could I still help neighbors and friends on the side? Sure. Would clearing urinal blockages in Critter Country and fixing leaky pipes in Fantasyland not be helping my neighbors understood more broadly? Of course it would be. But I can’t help but feel that I would slowly lose my grip on the real importance of my work: Disneyland patrons can find another bathroom; a single mother trying to juggle the needs of her children and home only to discover that her one toilet is backing up, can’t.

The greatest legacy someone can have won’t be found in social media virality or celebrity, but in the small moments of meeting the needs of their neighbor.

So not only do I a) do work that is in demand and helps train and form my interior world such that I am made whole and learn to be happy in this life, and b) that gives me the skills to have a bit of mastery over my own home and environment, I c) also do work that establishes me as a dependable individual to my spouse, my family, my friends, and my neighbors which in turn gives me a sense of self. I make little things around me whole, I become whole, and I get to share from the abundance of this wholeness with those around me, and this becomes my legacy.

The Money

“And now you’re telling me I get PAID for all this?!”

Boy, am I.

I won’t belabor the point here: there’s good money to be made in the trades. Really good. The biggest house I’ve ever worked in was the former CEO of FedEx. A nice fella and a personal friend of St. Teresa of Calcutta, as it turns out. But the second biggest house I’ve ever worked or stepped foot in was the house of a highly skilled, in-demand farrier. You know, the folks that make, install, and replace horseshoes. On horses. He travels the country and the world plying his trade, even custom making orthopedic horseshoes for equines that have sustained hoof or leg injuries and the dude makes bank for doing so.

Mileage is going to very, of course. A plumber in Manhattan probably makes more than a plumber in Montana, but a farrier in Montana might make more than a farrier in Manhattan. Availability of particular careers in your local market are going to fluctuate. But there is money to be made across the trades, and the skills you learn you can take with you to other markets should you decide to move. Many of the plumbers I work with in the Atlanta market make at or just under six figures. But an annual salary of $75,000 in other parts of the state or country could give a person a very comfortable life.

In Conclusion

Talking about the trades as valuable purely in economic terms is NOT an effective way to drown out the “follow your passion” siren’s song that is being sung by our culture. We have to conceive of them in a far more robust fashion, as actually fulfilling the deeper longings of the human heart, if we expect our kids to see trade work as a viable, respectable, and even noble option alongside a four-year college degree.

Skilled trade work is available; it has the distinct capacity for integrating your entire being; its dutiful practice can (and will) train your morals, emotions, and intellect along with your senses and spirit; it makes you a dependable member of your family and wider community; and on top of all of these benefits, you can make good money. Somewhere along the way, one might be pleasantly surprised to discover that this work, work that absolutely was not what they had conceived of as their “passion,” is something they have become passionate about.

One thing I want to emphasize before ending this gargantuan post is that the “Becoming” sections are not directly tied to wage labor. Blue collar jobs don’t have the monopoly on this interplay and mutual formation of the inner and outer worlds. Practices — voluntary labors — that recruit and integrate your body, your mind, your emotions, your morals, and your spirit are available to anyone. Gardening in your yard or your small apartment patio; rebuilding an old car; a martial art that emphasizes sparring; woodworking; running; art; music. You can do these.

I know that this was long. A labor unto itself. If you’re still with me, you are clearly a saint, a paragon of virtue, and eminent in holiness.

Thank you for taking the time to read and thank you for indulging my gripe at the beginning. I hope the juxtaposition of how the trades are normally marketed and how I’ve presented them here was worth the effort, and I hope that I’ve given you a springboard for considering the trades in a better, fuller way, one that makes skilled labor a commendable option for your own practice or as a career of choice for the young folks in your life looking for what they want to do for a living.

This is great. As an architect, I’ve long been in awe of skilled trades - all of them. People get sh*t built. AI can’t do that. I recently heard a fantastic podcast by a climate journalist who became an electrician during the pandemic so he could more directly contribute to the widespread adoption of clean energy. I encouraged my college-student son to listen, but though he works hard in school, he didn’t think he’d want to work *that* hard. 😂 He’s actually in great shape and could easily handle it, but he has to figure that out for himself. Young people today are conditioned by social media and sports betting, both of which promise easy money for little labor. Though my son is minimally online he’s not immune.

Fantastic article! I am a auto technician by trade. When I started at a trade high school I thought I would be an electrician or a carpenter. As I went through the automotive program I thought “this is cool! I want to work on cars!” 33 years later I’m glad I made that choice. It has introduced me into many other forms of trade. With encouragement from my wife I have built entertainment centers, wired my own electricity, fixed our own plumbing and our HVAC system. I have used this learned knowledge to help my neighbors with frozen pipes and built a stage for my church. Helped my kids friends with car issues and loaned tools to friends who couldn’t afford their own but had the talent to use them to help themselves. Money was a secondary thought when I started out. Come to find out you can make 6 figures being a “grease monkey”. Lol With a trade you can literally move across the country and not worry about being employed because someone is always hiring due to the scarcity of a qualified person. Thank you for this writing, hopefully more people see it!