The title of this newsletter is from Taylor Swift’s hit song “Blank Space”. What for her was a reference to the toxic behavior of a jealous and vindictive lover has apparently become Apple’s goal.

If you’ve been on the internet in the last 24 hours, there’s a good chance you have had the new Apple iPad ad roll across your screen whether you stopped to watch it or not. Apple CEO Tim Cook shared it to his X and it’s…well, if you have not seen it, here you go:

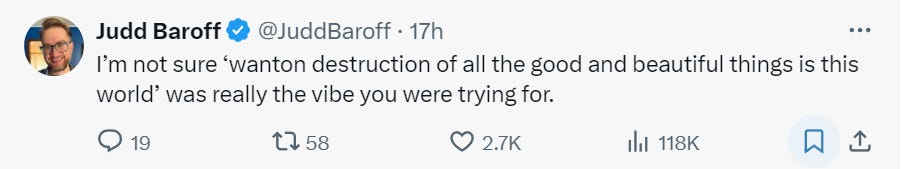

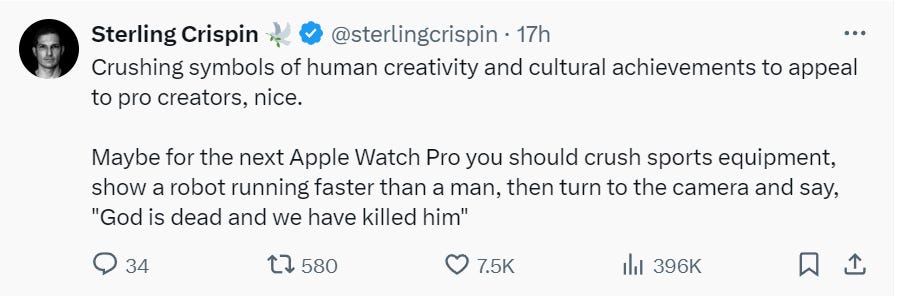

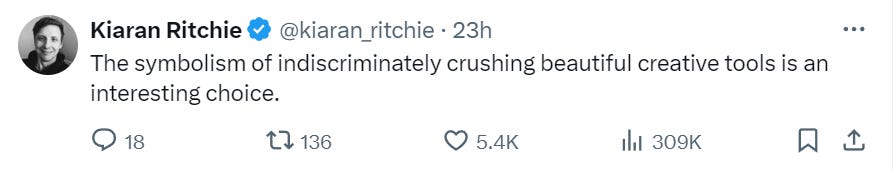

If it’s not immediately obvious to you that this is disturbing or why it should be, take a gander. A sampling of the comments left under Tim’s post on X:

And a particularly poignant response,

The comments are overwhelmingly negative. Comment sections rarely elicit this level of uniform response. And perhaps this uniting-in-disgust is more miraculous than the newest piece of glittering technology Apple has churned out. Silver linings and all that.

“Your predecessors showed us their dreams”

Apple’s founders had a dream of taking computational power and putting it in the hands of the everyman, not to make them dependent on a technocratic bureaucracy but to maximize their agency. It was a good dream. Human flourishing. Technology as a tool of decentralization and autonomy-granting competence.

As Ivan Illich would have said it, the dream of a convivial tool.

By “convivial” he meant that which “enlarges the range of each person’s competence, control, and initiative.” “People need new tools to work with rather than tools that ‘work’ for them,” said Illich. “They need technology to make the most of the energy and imagination each has, rather than more well-programmed energy slaves.” He wanted anyone involved in designing the next generation of tools to keep the good of the tool users in mind, to invite, through their design, particular human use. Namely, use that would habituate and bolster virtue, that would put them in healthier contact with the environment and people around them, that would “make the most use of the energy and imagination each has.”

It would appear that Mr. Cook and his team have not considered Illich.

“You showed us our nightmares”

The nightmare of, as Illich put it, becoming “accessories of bureaucracies” now seems to be Apple’s dream. Or at least this kind of deskilled, anti-matter, techno-bound dystopia, the kind that produces citizens dependent on bureaucracy, is what many are reading into the ad. I don’t know that I can accuse Tim Cook or anyone of Apple’s executive team of this intention, but, regardless of intention, I think it’s fair to say that the ad they have produced has unwittingly announced the end — the telos — of their technology.

And the end — the limit — of disembodied creativity.

One thinks of the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, Sweeny Todd, when he was finally reunited after many long years with the tool of his trade, the straight razor. He opened the box in which it was laid, raised his old friend into the sky, and exclaimed, “At last! My arm is complete again!” I have a hard time envisioning Sweeny Todd, or anyone at all for that matter, being disburdened of their tool and instead raising a tablet into the air and saying anything close to the same.

in his The World Beyond Your Head gives the example of early Mickey Mouse shorts versus the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse episodes of recent years. In the former, the material world is constantly threatening to overtake a bamboozled Mickey & Friends. No object in their vicinity was ever safe; nothing could be taken for granted. Each item was rich with opportunity for foibles, for frustrations, and they regularly resulted in fisticuffs. And boxing is just the right response: the various foils that the world’s favorite rodent protagonist concocted were physical. Mickey was forced to engage with the world, muster up what competence he was able, and with his own mixture of spunk and ingenuity overcome his material issues.Not so with Mickey Mouse Clubhouse. As the frustrations and dangers of the material world threaten to rain on the Disney parade, you will not find any of the gang muscling their way through the difficulty. The 1930s shorts which were brimming with comedic moxie are no longer. In the new millennium, all one needs to do is call out with full voice, “Oh, Toodles!” And from the sky drops a cutely designed Deus ex machina packed with perfectly crafted, ready-made solutions. The Handy Dandy Toodles, a floating robot that comes to the Fab Five’s rescue in each episode, offers one of four possible solutions to the various problems the crew will face. It is entirely unnecessary for them to put up their mitts, roll up their sleeves, or otherwise engage with the problem in any thoughtful way that recruits their skills (assuming they have any at all). Pain averted, frustration avoided, no intelligence needed. Oh, the ease and convenience of frictionless existence!

My point is not so much to attribute malicious intent to Disney, but to say along with Crawford that baked into the way these characters are depicted dealing with their environment are assumptions about how the writers think about life. Their presuppositions are seen through the cartoons’ actions.

Apple, it seems, has done something very similar with their advertisement.

So then, how do Toodles or the new iPad (or at least the way it’s advertised) differ from Illich’s convivial tools? Rather than enhancing human competence and cultivating a person’s faculties, these tools put further layers of mediation between the individual and their environment and other people around them. In the ad, paints and busts and instruments and models and books, games and lamps and speakers and televisions and metronomes and chessboards, each of these symbolizing entire worlds of craft and creativity, are being crunched together and in their place is left a simple, sleek device.

The message is clear: this new tablet contains creative multitudes. It purports to grant unprecedented access to the brilliance of all these disciplines. There’s a Tower of Babel comparison to be made here somewhere but I haven’t quite worked it out yet. Perhaps that’s a future newsletter. The question is: can Apple deliver on their promise? If Babel is any indication, the answer will be a resounding “no!”

“Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools.” Professing themselves to promote competence, they became masters. And we the slaves.

We are on a trajectory quite like that seen in the animated Mickey cartoons, from attentive mastery to atrophied and mastered, reduced only to our ability to choose from a selection of digitally represented, pre-packaged options rather than to shape the environment around us, which is characteristic not only of humans but also of certain animals. By further separating us from the material universe in and around us, the values habituated in us by our consumeristic culture threaten to, and, indeed, are already doing the work of, somehow making us even lower than the beasts of the field.

Truly a nightmare dressed like a daydream.

Just how far can disembodied creativity take us? Can creativity that is disembodied, accessible only through a glass screen and its precise manipulation, truly be called “creative” in its fullest sense? Is our definition of creativity too small? Can it become capacious enough to bring into its meaning whatever Apple is advertising that it can do? Where is the line at which this sophisticated piece of hardware ceases to be a tool for creative endeavors and instead crushes human capacity? There are no easy answers. The conversation, started many years ago by much smarter men, does not appear to be ending soon. In fact, it may just be getting started in earnest as more people feel their agency slipping from their fingers. I certainly don’t have an answer, but the majority of those commenting feel — and I with them — that wherever the line was, this ad has crossed it.

As someone who does a good deal of thinking around issues of human work in the world, this ad was very interesting to me. As we approach summer, my plan is to further clarify my stance on technology, tools, and their relationship to human flourishing. I’ll be reading (or re-reading as the case may be) Matthew B. Crawford, Paul Kingsnorth, Ivan Illich, Marshall McLuhan, L. M. Sacasas, Jacques Ellul, Albert Borgmann, Michael Polanyi, Iain McGilchrist, Neil Postman, Hartmut Rosa, and others. I’ll also read from certain e/acc (“efficient accelerationism”) writers.

None of them exhaustively, most likely. I don’t have that kind of time. But these seem to be some of the major voices that will shape a phronema calibrated to human flourishing, that can engage with our modern technological quandaries in a way that prioritizes people over products. In the coming months, look for my newsletter to engage with these thinkers as I work through my own thoughts and perspectives.

Perhaps at some point there will be revulsion. The other day I went to a Barnes and Noble and they have quadrupled their vinyl record section. Paper books continue to out sell e-books and Kodak is making more color film than in the last ten years.

This is a problem for the creative arts. It’s also a problem for healthcare - and more insidious, because there’s a strong push to eliminate the subjective messiness of human clinicians. You really want to trust your health to one of those? I regularly write and read about medicine and the machine. I don’t see any tides turning there.