A number of weeks ago I sent out the first of my essay trilogy published with Front Porch Republic covering the topic of craft and theology, followed a couple weeks later by my second essay in that series. I am now sending to you my third and final installment in this series.

This originally appeared on Front Porch Republic on December 27, 2023.

In the two previous pieces, I’ve proposed that a renaissance of craft informed by theology (and vice versa) is upon us and identified schools that are busy, or soon will be, making craftsmen-theologians who will become our future maintenance technicians and clergy and theologians. But the question remains: why is this renaissance happening now?

The answer isn’t an easy one. Indeed, there isn’t really a single answer. We find ourselves at the confluence of several rivers wending their way through history, each with its own unique banks and sedimentary layers numerous enough to occupy researchers for decades. An oil spill’s worth of ink has been spent describing their various features–our collective rejection of blue-collar and manual labor in favor of professional, service, and knowledge work–and now more is being spilt on what’s coming down the automation and AI pike.

In reality, this isn’t a new phenomenon. This tectonic shift in our culture’s attitude toward manual work reaches back to industrialization, and Christians have been thinking about the meaning of our bodies and our work since the early church. I stand no chance of adequately addressing the economic, social, moral, political, philosophical, and spiritual facets. Thankfully for us, other, better read, unquestionably smarter individuals have already been chewing on answers, so I’m going to rely on them for help.

In the final of five discussions on the Greystone Conversations podcast, cultural critic and philosopher of technology L.M. Sacasas suggests that the Arts and Crafts movement of the mid- to late-1800s, a reactionary movement against the cogs and wheels of industrialization as it clanked its way across Britain and America, was an early iteration of what we’re witnessing now. He says, “There’s something ultimately unsatisfying about the premise that all that we need is more cheaply available stuff.” Ultimately, this is what so many of our modern technologies are aimed at, and by developing them and accepting them into a place of daily use, we have willingly made an exchange, a bargain with the reality handed to us by our forebears. “[W]hat seems to be the underlying bet, as it were, or wager,” Sacasas continues, “is: an abundance of stuff, virtual or otherwise, is going to be sufficiently satisfying as a tradeoff for fewer skilled jobs, fewer opportunities to be not only a consumer but a person who creates, who works meaningfully, who has tasks to accomplish, and can feel a measure of satisfaction for having accomplished them.” There is a growing sense among many for the last century and a half that we definitely bet on the wrong horse.

We thought we wanted an easier life. We thought we wanted to be more comfortable, more often. We thought that in outsourcing the difficulties, frustrations, and exertions involved in learning skills and wielding them to earn our daily bread, we’d save ourselves time, time that we could spend in other, more enjoyable, leisurely pursuits. Perhaps we did want these things, but we weren’t ready for what it would cost us: our agency and, with it, our sense of identity. Now we have all the time in the world, and we waste it doomscrolling; umpteen hours per year freed up from physical toil only to be inflicted with crippling emotional toil; we gave up gripping tools and lost grip of ourselves. We now endure work we can’t stand, likely for less-than-satisfactory pay (or maybe we don’t have virtue enough to live within our means? or both?), with a thinning sense of self and a thickening cynicism towards others.

And is this not an echo of the sin of our parents in the Garden? The Garden was the training ground for humans to rightly order God’s good creation. As they paid attention to the needs of the plants and each other, our parents would cultivate fertility in the soil and virtue in their souls. Vines and branches and bushes and roots would produce the food, and their own spirits the righteous fruit, that they would take, eat, and see that the LORD is good. Their work was material and it was moral. Attentiveness to the land’s needs would result in self-giving labor to meet those needs and see it bear its fruit. Moral work was as important as the physical work which enfleshed it. God’s presence in His Creation was the context in which humanity would flourish; virtuous human labor was the context in which Nature would become flourishing Garden.

Perhaps we can look at the serpent’s temptation, among the many ways that it can and has been understood, as one which lured our parents away from that labor by which, already made in God’s image, they would become formed into His likeness. The produce which God had forbidden was ready-made hanging on a tree, and under the deceiver’s influence Adam and Eve thought they saw an opportunity to have their fruit and eat it too: to become godly by consumption rather than slow, virtue-producing labor. That’s how the serpent postured it. They could skip the sweaty soil-work, skip the torturous soul-work, and have what they were ultimately working toward anyway: holiness. This word comes from the same Old English word from which we also get the words “health” and “whole.” The fruit, the serpent told them, would fill their bellies labor-free and, with only a few mastications followed by a smooth swallow, mystically bestow upon them the fullness of the stature of the LORD their God.

The disintegration began. Woman and man turned in on themselves and against the other; the attention Adam had once paid exclusively to Eve and Eve to Adam now rested on their own being: the cold shock of nakedness made them gasp for air. Vice had been introduced to their souls, and the warmth of life exchanged for frigid death. The soil which had been ignored in favor of available produce now had a weakened structure which humans would forever struggle to rebuild and maintain. Thorns now lay over neglected ground. The God-haunted Garden which had been the place of habitual, incessant fellowship with the Creator was no longer safe. Tree trunks now served as hiding spots.

We, too, have become a labor-avoiding, consumptive people, and we suffer the same disintegrating effects as our parents. We sense that we are not whole, that there is no health in us. We hide from God and neighbor behind the material world–particularly as it is expressed today in digital form–which was meant to be the means of our communion with others. Perhaps we are beginning to realize that we are gaining the world and losing our souls and that we don’t like it very much at all.

In their exploration of Henry David Thoreau, Henry at Work, authors John Kaag and Jonathan van Belle say that Thoreau was among the American thinkers who were ultimately considering the nature of work and life as I am doing here. And why were they asking it? “In part, it was the feeling of rootlessness that many workers in the United States were experiencing at the time: the migration to cities in the Industrial Revolution destroyed family farms and tight-knit communities, and it left many people unmoored and unable to hold themselves together.” Are we not in a moment quite like this one? Rootless? Unmoored? Untethered from anything resembling a reality that we’d like to inhabit while we fall to absolute bits?

The frictionless existence we were promised, one that freed us from slavish obedience to place and tradition and family bonds, turns out to be one in which we amorphously float about in a gelid atmosphere longing for the halcyon days of family farms and quaint communities. In another of the Greystone Conversations, Joshua Klein rather pithily says that “without friction, there is no traction.” This seems right to me. Industrialization isn’t forcing us into cities, but digitization is forcing us deeply into ourselves and further away from each other. We are not burnt by failure or hate, but neither are we warmed by success or love. We simply endure the cold solitude of abstraction until passing from this life.

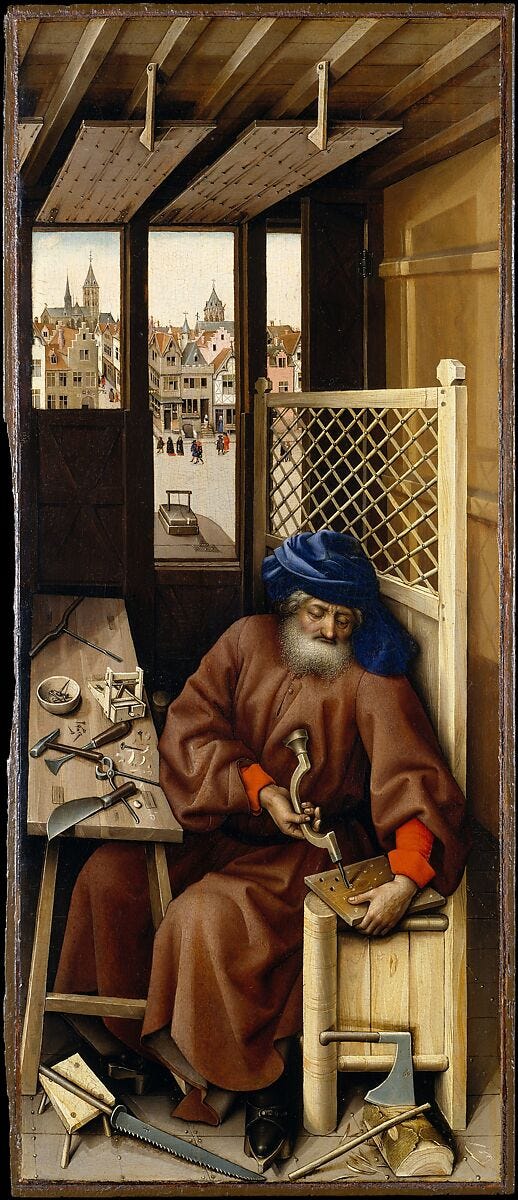

Saint Francis of Assisi, Hugh of St. Victor, Thoreau, Adam and Eve: these landmarks point the way forward. It is a way deeply engaged with the good creation of God, one which forms us as we form things, one in which we grip the world and get a grip on ourselves. St. Francis could only rebuild Christ’s Church after rebuilding Christ’s churches. Hugh could only understand philosophy if it included the mechanical arts as both revealing and enacting Wisdom in the world. Thoreau experienced manual labor as rooting us to our place and thereby introducing to us a life of true economy–of family, land, and home. Adam and Eve rightly ordered the Garden for a time and found that place to be nothing less than a sacred temple, a means of deepest fellowship with God.

Theology, at its root, is the question of who God is and, as a consequence, who we are. The mechanical arts allow us to engage with the universe’s Creator by that which He created, to discover who we are as we rightly order the material world, and to become rightly ordered as a consequence. Both center on God, and both reveal to us our identity. They are not separate projects. The unmoored, untethered existence towards which we are barreling and which, indeed, we are creating, is precisely the one that pastors are tasked with speaking into, and they must speak with feet firmly planted on the ground, fingers firmly wrapped around reality, gripping and gripped by the world that we live in.

So why is this renaissance happening now? It’s the same as asking why God does any of the things He does, whenever He does them. Who can explain the providence of the Lord? Who can know the mind of God? Perhaps we’ll be able to answer the question in retrospect, but even then, just barely. All we can hope for now is to be students of the times and to follow the Spirit as He moves. Clergy and laity alike must fight to remain situated in and engaged with the world God has placed us in, conscientiously forming the world with the understanding that it reciprocally forms us.

I’ll end with a quotation from the deuterocanonical book of Sirach which, I think, nicely sums up what I’m trying to articulate:

“[Tradesmen] rely upon their hands, and each is skilful in his own work. Without them a city cannot be established, and men can neither sojourn nor live there. …[T]hey keep stable the fabric of the world, and their prayer is in the practice of their trade.” (Sirach 38:31-32, 34)

May God raise up more clergy and laity who can, by their careful study and dutiful labor, “keep stable the fabric of the world.”

I sincerely thank those of you that have read all three installments in this trilogy and hope that it has served as a spark of optimism in a bleak landscape the threatens to swallow the light.

Praying for health and peace in your home,

Nate

How heartening to read what you share here Nate. Thank you. It made me think about why I often find myself craving to cook for my family even if, in my part of the world (the southeast Asian Global South), middle class conventions include having a hired cook at home. Recently I discovered, I prefer defying this convention for the sake of my and my family’s soul. I couldn’t put into words why my instincts pointed in this direction but your essay helped me see, that crafting, whether with wood or food, is a powerful daily way of touching God and unveiling our best, fullest selves. Thankful for this reminder.

A very thought engaging article, Nate.

Both my boys are skilled tradesmen by choice and I am going to forward this to them. I love the quote at the end -

“[Tradesmen] rely upon their hands, and each is skillful in his own work. Without them a city cannot be established, and men can neither sojourn nor live there. …[T]hey keep stable the fabric of the world, and their prayer is in the practice of their trade.” (Sirach 38:31-32, 34).

Society has elevated the "professional, knowledge based" jobs to the point of disdain for anything "less" such as skilled trades, yet very few even give a thought to the fact that none of what we have now would even be possible without them.

Also, love how you integrated the theological points here, especially tying in the Garden scenario. Never thought of it like that.

Thanks for this essay.