Cloacina: the ancient religious need to be clean

You would like to leave the bathroom, but you cannot. Your gut is rumbling. The incessant churning of an internal squall keeps you anchored as you ride wave after miserable wave. Was it bad cheese? Did the fish ferment too long? There's no telling and, frankly, it doesn't matter now. What's done is done. Desperate, your soul evacuates a prayer with the force of your soured bowels,

“O Cloacina, Goddess of this place,

Look on thy suppliants with a smiling face.

Soft, yet cohesive let their offerings flow,

Not rashly swift nor insolently slow.”

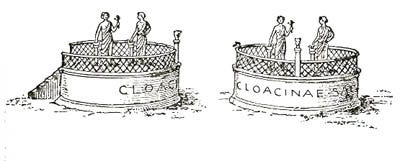

No one quite knows when she joined the Roman pantheon, but it's thought that the Etruscans which came before honored the goddess Cloacina. Over time she became merged with Venus, making Venus Cloacina both goddess of sex and fertility and the deity which graciously ruled the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's serpentine artery that discharged excess rainwater into the Tiber. How did she come to be the Roman sigil of sewerage?

Folk legend surrounding the construction of the Cloaca Maxima—literally the “Great Sewer”, which began perhaps as early as 600 BC—tells us that workers discovered the statue of a beautiful woman face down in the murky trench. Unsure of her identity, they stood her up at a nearby shrine. One day, as a woman passed the shrine, she found the goddess face down on the ground and thinking this unfit for deity, set her upright again. The day following, workers found her face down in their trench…again. It took finding her in the muck multiple times for them to say, “Ah-ha! She likes the sewer we're building. She wants to watch over it!” So obvious! In another story, one of the workers toppled into the waters and was saved from drowning by the clement Cloacina. She became associated with the purifying and cleansing properties of water, the concept of “purity” acting as the through line to sex and the marriage bed, and with time Venus Cloacina's patronage was crystallized.

Humans have sought spiritual and physical cleanliness for millennia, as the existence of deities embodying the respective impulses shows us. Yet the ancients did not see such a great chasm between the two: is what is done with the body not a spiritual act? Even the Bible contains laws, given by God and in line with His holy ways, dictating where an individual may pinch one off. When the Psalmist wrote that “if I ascend into the heaven, thou art there,” and, “if I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there,” he might have rounded out the verse by saying, “if I be sat on the porcelain throne with gut a-roiled, even then thou art with me.” My sense is that what we expel from our bodies and where it goes will be of fascination to us until the eschaton. Indeed, es-scat-ology. The rear end times.

Despite our reluctance to link the two, the pair of sex and sewer didn't end with Cloacina. Not by a long shot. Jessica Leigh Hester in her delightful book Sewer notes that while the pipes may be out of our direct line of sight, tucked away from our consciousness until inopportune times, “it's not a realm distinct from ours. It's a place we have built” and use as we see fit, and if you ask your service plumber what exactly can (or cannot) fit down a sewer line, it's not long before a sex toy makes the list. Robert Macfarlane in his Underland: A Deep Time Journey observes that we utilize subterranean spaces “to shelter what is precious, to yield what is valuable, and to dispose of what is harmful.” I wonder if a flushed fleshlight falls under the first or final category? Either way, it seems we are not as far removed from Venus Cloacina as we might like to think and, if what is found in our sewers are any indication, we could stand to learn something of her purity.

Monk dung: medieval sewerage development

Development of plumbing was a slow-going process. There wasn't much to speak of between ancient Rome and the medieval era, but leave it to the religious to bring us the next great leap. By “religious” I don't mean worshippers of Cloacina. Rather it was the Jesus-worshipping Cistercian monks with their inherited hydraulic mechanical and engineering practices who applied what they knew in unique ways both in and under their monasteries. Which, of course they would—when the monks weren't praying, they were busy about the work of bread baking and beer brewing and cloth manufacturing and other trades that required water-operated millwheels. And there were guest house walkways to scrub and meals to cook and myriad other uses for water that don't need explaining.

But what has this to do with sewerage? Before I can answer that, you need to understand that monasteries and other medieval architecture would sometimes be built not just next to streams of water, but on them. There are obvious advantages to this, among them: easily accessible fresh water delivered through the structure, and dropping deuces straight into the drink. But these buildings weren't always directly atop running water, and even when they were, nature can be frustratingly fickle and withdraw her provision. Such was the case with the monks at Waverly Abbey in the early 13th century. Brother Symon and his fellow religious were under duress because their aqueduct-feeding spring had run dry, but there were habits and dishes to be washed and poops to be taken, by golly. His solution? Brother Symon created channels that diverted water from a number of different sources into a “living and perpetual spring, made not by nature but by art.” A masterpiece inspired in no small measure by the Giver of Living Water.

Whither wended these waste-waterways? After leaving the monastery grounds, to the local fishpond, naturally. I had a pond across the road from my neighborhood growing up, one fed not by a spring but by the city, with reclaimed rather than living water. It would get so polluted with mallard mung that during the summer you could smell it from the moment your foot touched the path leading into Hartwell Park. One might be tempted to think that an abbey sending its crap current to the fishpond seems an unsavory thought. Surely it’s an unhealthy practice? Not so, says Roberta J. Magnusson in her Water Technology in the Middle Ages. There are two serendipities she identifies: one, for fishponds it “may have been beneficial, inasmuch as excreta can increase yields by nourishing the plankton on which the fish feed”; and “the millwheels would have provided (inadvertent) wastewater treatment as they aerated the sewage.” Accidental genius.

We will have to ignore the other monastic plumbing developments like the sophisticated three-tiered water systems, windlass-actuated sluice gates, complex distribution networks, early water filtration attempts, and other technologies that are commonplace—even quaint or vintage—to us now, but then were centuries ahead of their time. Suffice it to say that monks may not have been sexually active, but they recovered something of Cloacina's purity and brought plumbing from the Bronze to the Bright Ages.

A sewer is a mistake: a modern social commentary

On the whole, we are thankful for what our monastic forbears afforded us. And the Cistercians weren't the last Englishman to plus the plumbing trade. Those born royal and those who became so by their achievements have shaped us by shaping where we go to cleanse our bodies of its waste and where we send it.

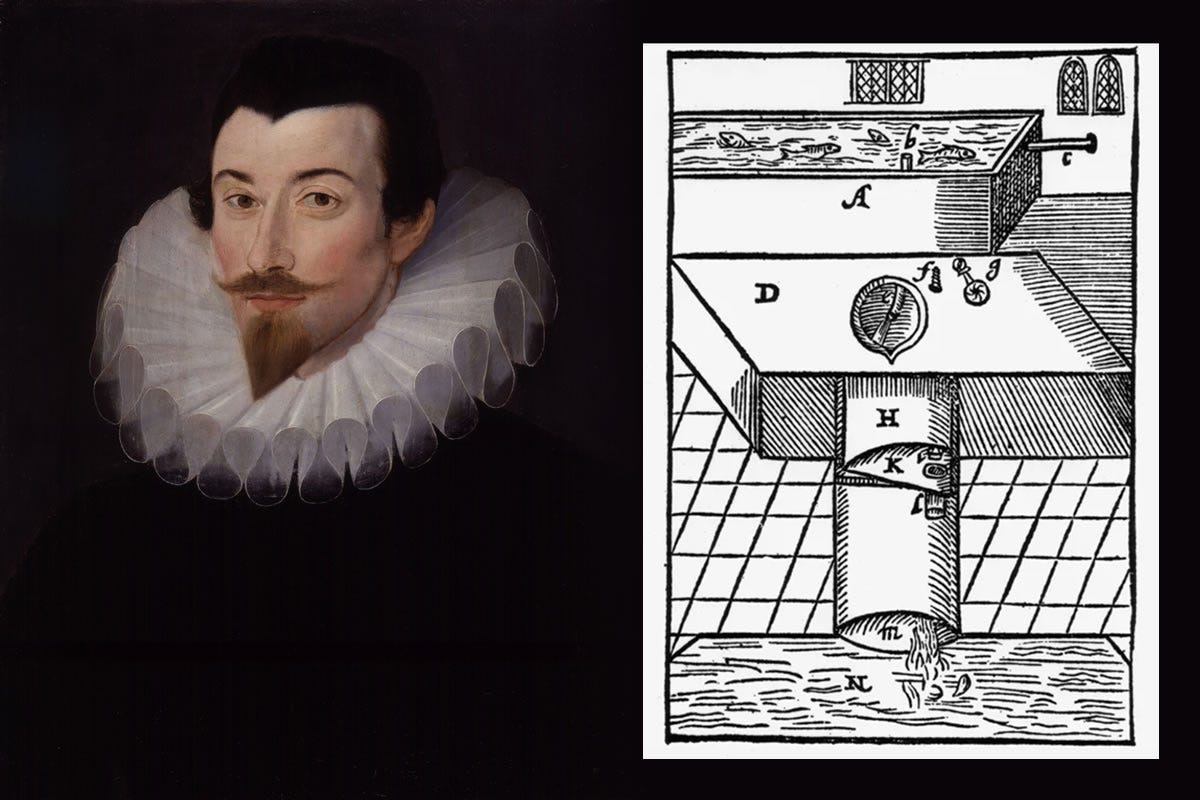

Take the real inventor of the modern toilet, Sir John Harington. Flush toilets have existed in some form or fashion since the medieval monasteries, but you weren't going to find Brother Symon perched on a Kohler or a bidet. Most residences weren't built on or even near water like the monasteries. Indoor plumbing as we know it was still a future development. Sir John, godson of Queen Elizabeth, wanted to make the indoor defecating experience a more pleasant one and thus developed the ajax. Precise dimensions, materials, and directions for building this device, along with pictorial diagrams that must have inspired IKEA’s own, were recorded by Harington for our benefit—a tank for water with a lead pipe leading down to an oval bowl, the water controlled by a cock or washer.

Religion once again played a role, if not in its development, then certainly in its marketing. Harington wrote in his A New Discourse on a Stale Subject Called the Metamorphosis of Ajax, “He that makes his belly his God, I wold [sic] have him make a Jakes [a toilet] his chappell [sic],” and mentions that the heretic Arius died whilst dumping, so be sure “to have godly thoughts” while answering nature's call. And how! The Queen liked her godson's ajax so much that she had him build one for her at her Richmond palace. But as the year 1600 neared, the ajax hadn't caught on, at least not under that name; the water closet, however, was growing in popularity as cities grew in population.

Jump a couple centuries to 1865. English optimists that expected the rise of a greater, grander London looked, of all places, to the sewer as evidence. Sir Joseph Bazalgette had been hired to overhaul London's sewers in the wake of The Great Stink, an event which makes my duck poop pond story downright cute. The banks of the Thames had become so encrusted with human waste that when in the summer of 1858 Mother Nature decided to give streams of sunlight and heat instead of water, she put the city out of commission. Officials could be spotted escaping the Houses of Parliament, not to evade the stench of politics but of poop. Bazalgette's project of remedying the situation was met with mixed reception. But after his expansion of the city's sewer pipes in both diameter and range, and the construction of Crossness Sewage Treatment Works, foremost among the so-called “cathedrals of sewage,” Londoners that were reluctant to hope against hope were glad they'd done so. The Illustrated London News wrote, “The work will be of material use to London, not so much now, perhaps, as in the future when I hope London will have become one of the healthiest cities in Europe.”

Not everyone was so enthused with plumbing's trajectory. A contemporary of Bazalgette, Victor Hugo dedicated an entire book in his Les Misérables to Parisian sewers. Even if he'd known that exciting developments were afoot (abum?) just across the English Channel, his rather pessimistic diagnosis of the state of sewerage and the human condition would have been welcome fuel to Bazalgette's optimistic fire. “The history of men is reflected in the history of sewers,” Hugo rightly wrote. “The sewer is the conscience of the city. Everything there converges and confronts everything else … Each thing bears its true form, or at least, its definitive form. The mass of filth has this in its favor, that it is not a liar.” For Hugo, the sewer is apocalyptic, all-revealing, a truth-teller showing us the worst of ourselves and little of the best. “The sewer is a cynic,” shouting from below our hypocrisy and our inclination toward self-interest. Not a flattering picture. So what of our best is to be found in the dank shade of a poop pipe? The potential fertility of our dung. But what do we do with what he calls “golden manure”? We flush it, of course, and starve our fields while making a gutter of our seas. “Hunger arising from the furrow, and disease from the stream.”

Hugo pithily sums up his thoughts on sewers with this famous line: “A sewer is a mistake.” It wasn't too far into my plumbing career that I found I might agree with him.

Love in the place of excrement: a story

On an overcast day in the Spring of 2016, I stood with my job lead in the verdant front yard of a funeral home. John cast a glance at the structure, then back to the road; to the structure, to the road again. His eyes narrowed as he cogitated. The sewer main serving the multi-story building was backed up, a problem when you have embalming fluids and human waste from both the living and dead to dispose of. Toilets, floor drains, and sinks threw a synchronized tantrum, unwilling to swallow what was being fed to them. With a sigh, John walked to the side of the building.

Next to the front porch a 4-inch PVC portal rose from the soil: a cleanout, the pipe used to give plumbers access to the inside of the sewer main otherwise out of reach below the dirt. If you open a cleanout and it's dry, your clog is upstream; but if you find water waiting for you under the cap, the clog is somewhere between you and the sewage's final destination. John grabbed hold of the cap's raised head with his Channellocks and gave it a sharp twist, then with gloved hand lifted it out of the way. Satan's soup rippled up at us as if to wave. Our problem lay roadward.

The next move was to drop a camera into the cleanout and push it down the line until we hit the clog and couldn't push it any further. At that point, the camera head becomes a transmitter that can be located and will tell you where you need to dig. By Georgia state code, there must be one cleanout every 100 feet OR immediately following directional change exceeding 90°. The distance parameter is because the cables used to clear sewer lines lose torque the longer they get, and after 100 ft. they are nearly useless; the direction parameter is because elbows tend to be a place where solids congregate. In our case, it was a straight shot to the road but the camera head was roughly 150 feet away from the cleanout. We needed to dig the line up not only to relieve the clog, but also to install a cleanout at the code-specified distance.

John ascended his backhoe throne and commanded that dirt be banished to a spoil pile, revealing the 6-inch ductile iron sewer a couple feet down and about ten feet off of the sewer tap where the funeral home's sewer main connected to the city's. Preparations were made downstream of the clog so the 150+ feet of built up refuse could pass into the city sewer. All that remained was to open the line and let it flow. But how?

Ductile iron is tough, too tough to simply crush with a sledgehammer. We opted for a concrete saw equipped with an abrasive blade, which I was tasked with operating while John stood back. (Always a good sign when the lead puts distance between themselves and the job.) I started the saw and nervously lowered the blade onto the pipe. Sparks flew. Acrid smoke filled my nose even through my mask. Cockroach turd-sized bits of metal pelted my cheeks. And then ksst- a small spurt of water pissed out, the flow immediately thwarted. By what?

John decided that in lieu of cutting or sledging, he would use the backhoe bucket to crack the sewage-filled pipe. It was my turn to step back. He lifted and forcefully lowered the bucket thrice. Thud. Thud. CRUNCH. Satan's keg, pressurized only by gravity and volume, ejected its contents against the back of the bucket and created a liquid fountain rivaled only by the Bellagio's own. Browns and oranges and greens and reds fanned six feet into the air. The scent of shit and embalming fluid replaced smoke as the dominant odor. About forty-five dazzling seconds passed before it ended. And that's when I saw it.

Face down in the sewer trench, dully aglow with cloudlight caught in not-quite-water, was a... Wait, is it? Yep. That's a condom.

W.B. Yeats in his poem Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop wrote that “Love has pitched his mansion in/The place of excrement.” It's none of my business, really, as to how this modern accoutrement of sex got in the sewer line or what it had seen before floating amongst crap and corn, and I don't think this is exactly what Yeats meant about love dwelling in excrement. But it had something to do with Venus and it left me with a slightly icky feeling I couldn't shake, one that drew me a skosh nearer to an Hugoan sewer-cynicism. Since then, and no offense to her or the utility under her dominion, but since then I've been wondering at and questioning Cloacina.

Nate, you truly are a 'blue scholar'! What fun to read such a deep dive into history and your own experience. I know that there have been books written about the history of sanitation, toilets, etc. but I very much doubt that any of the writers shared your personal experience. Seems there is a book waiting to be written based on your articles! :)

Thank you for one of the most entertaining articles I've read in months. I loved the plays on words and the ties to history and literature and theology.