Shepherds of Decay

Asking Paul Kingsnorth’s question, “Is there anything left to conserve?” through the lens of composting.

Note: Some of you may have read this already. Most have not. I published this essay originally at my pre-Substack website in the beginning of June, but have made edits to better articulate my thoughts and clarify my ideas, include footnotes and more links, and improve the flow of the piece as a whole. Whether or not this is your first time reading, I hope you find it worthy of your attention. Even though I wrote it first, I consider this the proper follow-up to my essay “Lessons From the Compost Heap”: the same (or at least a similar) lesson, applied at a larger scale.

Thanks a heap for reading.

Memento mori. This potent Latin phrase meaning "remember your death" or "remember you must die" is a trope that serves as meditation fodder for most religious and philosophical traditions of the last 2,500 years, gaining its famous formulation from the lips of ancient Roman luminaries.

Legend has it that following on the literal heels of a Roman general in the after-Roman-military-victory procession would be a slave, repeatedly shouting over the joyous cries of the thankful citizenry to remind the general of his mortality. Whether or not this actually happened, I accept it as canon because it’s hardcore and I like it. More recently, the Judeo-Christian tradition that Western culture is founded upon presents to us the biblical Psalmist shouting over Christendom’s crowds, "Teach us to number our days!"1 slavishly following every victory procession from its being written until now.

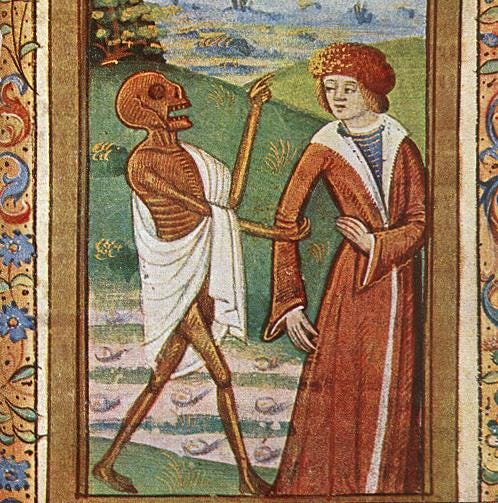

What began with representation in words soon came to be represented by image: the human skull. The image of the skull, emptied of all organs and stripped of all flesh and absent anything indicating life, was so imbued with the meaning of our mortality that its presence in art became the beholder's nagging reminder: you too will die. Simply a glance inspired contemplation of one's numerically limited days and the immanence of the grave. No words necessary.

There was in the art and cultures of yesteryear a certain incongruence between the symbol of death and its surroundings, a stark contrast of darkness and light, death and life. At the height of Western civilization, pulsing as it was with literature and art and theater and architecture and religion, the reminder of death was, if not exactly welcome, then certainly necessary. The West could get too big for its britches on occasion. Memento mori was there shouting over it all in a more-or-less successful attempt to instill humility. A reminder of death actually contrasted with the experience of abundant, vibrant life.

But I wonder whether this is any longer the case. What happens when everything around us — from entertainment to education, from literature to the laws governing our society — transforms into the symbol of the skull, emptied of and emptying all organs, stripped of and stripping off flesh, absent of anything indicating anything like life?

What happens when the culture becomes the memento mori?

Is There Anything Left to Conserve?

Paul Kingsnorth asked the question "Is there anything left to conserve?" in a recent talk and article for UnHerd. Peter J. Leithart, inspired to reflection by Kingsnorth's thoughts, also wrote on the topic. The answers they offer can appear bleak. In sum:

Nah.

Far from being a flippant response, two of our foremost Christian public intellectuals have looked at the circumstances of modern Western society and, perhaps despite a desire to give a happier answer, have responded in the negative. Others like the Rev. Dcn. Calvin Robinson and Matt Fradd have said the same in a recent conversation.

Asks Kingsnorth, "What, in this world," one in which humans are increasingly post-human; nature, post-nature; the wild, post-wild;

can we possibly 'conserve'? Nothing. In a culture which does not agree that nature exists, or that we have some basic, shared assumptions about reality, the question barely even makes sense.2

Salt in the wound — whether for preservation or insult — assumes flesh, but no flesh remains to be either salted or assaulted. The bones of Western culture have been picked clean.

For Leithart, Kingsnorth's prognosis rings true. "Kingsnorth is right," he says. "We must grasp the gravity of our moment. The West isn’t sick. It’s dead, and we should heed Jesus’s exhortation to 'let the dead bury their dead.'"3

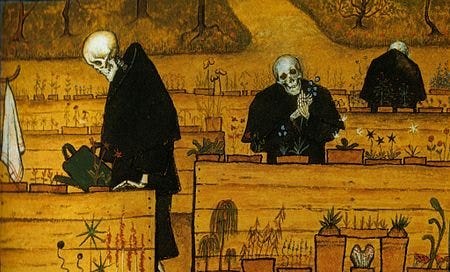

If this is indeed what we Christian Westerners ought to do, then I happen to know (and more recently to have joined the ranks of) those who are particularly adept at burying their own dead. It is a practice that goes back millennia. As veritable legions of their own fall at their hands, these rank and file grim reapers ennoble the death of their fallen by piling their bodies high and overseeing the slow deterioration of the ones they loved, the ones for whom they sweat and labored.

I am, of course, talking about gardeners.

Return to the Real

It didn't take much time after I began gardening to decide that I would likewise begin a compost pile. Not too long ago, taking the scraps from one’s kitchen and placing them alongside leaves and wood shavings in a heap that will break down to become next season's fertile soil was simply what was done. Those days are gone. It is now a choice one must make in opposition to the formation of our prevailing culture. Most urban and suburban areas have public sewerage infrastructure and trash collection systems that will take their waste away for them, and many, especially in urban areas, live one or more stories above the ground, comfortably separate from the humus or any thought of it.

If to “have one's head in the clouds” implies feet that have left the ground and reality along with it, then we seem more worthy of the phrase now than ever and certainly embody it more frequently. As our imaginations, so our structures. The requisite views of waste4 and earth that underpin the agricultural practices of yesteryear no longer inform our daily lives, a stark reality which would bewilder our ancestors. They could not have conceived that we would place dozens, even hundreds of feet between our own and the ground, or that the vast majority of people wouldn’t have at least a couple laying hens, goats, perhaps a pig, or even a dairy cow. As is said to Very Online People when they appear to others to have lost their grip on reality, our ancestors would likely tell us to “touch grass”: return to the real.

Composting, and gardening more broadly, is for me a sort of return to the real. A return to things as they have always been. But what is composting?

It’s not an act of conservation in the way we understand the word as applied to, say, the National Parks or other environmental initiatives. It’s not the attempt to preserve things as they are, to resist the process of breaking down, to keep things in a state of arrested decay. Conservation of this variety is put into place when what is present is valued and valuable, something deemed worthy of giving to our friends and children and perhaps to their children and grandchildren after them. The West, Kingsnorth and Leithart argue, is not conservable in this way. Fair enough.

However, it appears to me that there is a sense in which composting is precisely an act of conservation. The sense I have in mind is thermodynamic: to compost is to attend to the natural cycles of energy and entropy.5 Composting is the shepherding of decay and death, that among death there might be abundant life6 under the gardener’s watchful eye, a return to the ground, a better-than-magical transformation into the fertile soil of a future growing season.

By definition, to compost, far from ignoring or ameliorating death, is to go beyond passive acceptance and actively embrace its reality. I think most of us are broadly familiar with the concept — stuff breaks down and becomes soil — but allow me to briefly articulate this God-haunted process for the uninitiated.

I just got done cooking. I have in front of me the finished product — a meal; I also have in front of me a smallish pile of unused bits of ingredients from its preparation — scraps. Rather than wasting these uncookable soupçons by chucking them in the bin for someone else to deal with later, I take it upon myself to do something with them now: I place them (along with other scraps from other meals) into a heap on the side of my house.

Gathered into this heap are a number of organic items which can be broadly categorized as my "greens": a source of nitrogen, a bit of life left in them, e.g. a banana peel that is still yellow and a bit wet, fresh grass clippings; and my "browns": a source of carbon, basically drained of all life, e.g. dried leaves or pine needles, cardboard, hay, even the lint from your dryer screen. With some exceptions, what I bring from my kitchen is largely the former and what I rake up from my yard is largely the latter.

Two more key components: air and water. Water is the universal solvent, breaking down nearly anything that stays submerged long enough into its elemental building blocks. Air ensures that there isn't too much moisture — which could cause anaerobic conditions, a breeding ground for the wrong kinds of bacteria and interrupting the decomposition process — and, damp compaction avoided, allows oxygen to diffuse through the pile. I layer greens and browns together, add just enough water to make the pile glisten, stir it all together, and I am off to the disintegration races.

Also important to this process is the heat that is generated by the release of energy as familiar items are disassembled at the molecular level. These increased temperatures kill off weed seeds and disease pathogens. If it's cold enough outside, you might catch a glimpse of steam billowing up from the heap. On the other hand, if clouds of stench or of flies rise from the heap instead, it's likely too wet. No discernable heat and it's likely too dry.

There is much to notice, much to which I must attend. Composting requires my attention for attention joins me to the world, and it is only by joining myself to the world that I can care for and understand it and act in accordance with its sundry needs. A stark contrast to a life disjointed from the world, one with my head in the clouds.

Microorganism, insects, worms. All of these make their way into the pile to disassemble the mish-mashed assortment of refuse. Excreta and secretions of these smaller lifeforms feeding on the wet and dry morsels are deposited in the pile.

Stuff that mere days and weeks ago was orange and yellow and red and green and blue; stuff that was soft and prickly and fluffy and squishy; stuff that was wet and stuff that was dry: in due time, it all becomes what one can recognize as vaguely brown, somewhat dirt-y. Just a bit longer and all doubt is removed. It has become soil. Rich and crumbly and fertile, it is ready to give life to a new crop and a future harvest.

You'll have to look elsewhere for a fuller description of what's happening at the chemical and molecular level, but suffice it to say that on its face this is the sort of thing that one might reasonably expect to encounter in a spellbook. Or, more likely these days, a meme. "I took all of my food waste and lint and shredded newspaper and threw it together and now I can grow my plants in it." "Sure grandma, now let’s get you to bed.”

Especially in the age of high rises and pre-packaged food and the various systems necessary to provide them and the ways of thinking that come with it all, composting can seem a bit…absurd. Unnecessary, really. And yet it is, I think, exactly the framing through which we must re-ask Paul Kingsnorth's question:

Is there anything left to conserve?

Let the Dead Bury Their Own Dead

On Kingsnorth’s and Leithhart’s accounts, in the West at present we have what is dead and what is dying. I will direct you back to their respective articles to convince you (or not) that this is the case. For now, I assume it to be an accurate assessment. The skeleton of our civilization is clearly visible and the flesh that once encased its bones has dropped to the ground.

Grim as it may appear, is this not what a well-made compost heap requires? What is dead and what is dying? It is. My browns and my greens respectively.

Leithart in his essay lists off a number of civilizational cycles of life and death that have occurred through the ages, moving through the multiple examples of Israel's own life and death, and arrives at Pentecost: the Spirit of God descends with wind and fire and baptismal water and "propels the church across new horizons, breaking through old barriers and stirring dry bones."

If we are careful, we will notice once again that the elements necessary to composting have been invoked. The Spirit's descent and activity, air and water and heat.

Leithart ends his piece saying, "The West isn’t sick. It’s dead, and we should heed Jesus’s exhortation to 'let the dead bury their dead.' Our calling in the wasteland isn’t to conserve but to keep in step with the Spirit, hoping, boldly and joyfully, for resurrection."

This feels uncomfortably passive to me. I would like to suggest that "the dead" in the case of the West is the corpse of Christendom and therefore it is not “theirs.” For those of us who are Christians, these are "our dead." Our calling in our ancestral wasteland, then, is precisely to conserve it, not by arresting decay but by attending to and shepherding it, in which work we will find ourselves in step with the Spirit, enacting, boldly and joyfully, the promised resurrection.

All around us is the image of the skull. We are in a living memento mori. Everything and everywhere ceaselessly depicts for us in word and image the demise we find ourselves inhabiting. We do not look upon the skull from without: we observe it as we dwell from within.

Yet composting habituates in the practitioner an unanxious embrace of death. The real end of one thing can usher in the real beginning of another. God, just as much now as He did on Pentecost, has provided for us all that is necessary for life and godliness in this and every age. We have what is dead and what is dying, and He has sent to us His Spirit which gives us air and moisture and heat. It is only left to us to prayerfully and care-fully place it all together and, with feet soberly on the ground, to attend.

We Christians, God as our helper, function as both the gardeners of Western civilization, cultivating its rise and enjoying its fruits and now amassing its remains in the compost pile, and its heap-dwelling microorganisms, responsible for taking the various bits and pieces of dead and dying culture and decomposing them into the precious stores of nutrients and energy that will become the fertile soil of a future crop and its harvest.

When the culture becomes the memento mori, we become the shepherds of decay.

Psalm 90:12 KJV

Paul Kingsnorth. “Is there anything left to conserve?” UnHerd, https://unherd.com/2023/05/is-there-anything-left-to-conserve/. Accesed May 30th, 2023.

Peter J. Leithart. “Christianity: Neither Revolutionary nor Conservative.” First Things, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2023/05/christianity-neither-revolutionary-nor-conservative. Accessed May 30th, 2023.

I briefly address what I think is a better view in my essay “Lessons from the Compost Heap”. In short, ontological waste does not exist. Humans waste (a verb), but thinks are not waste (a noun). Marc Barnes, in his conversation with Shawn and Beth Dougherty, brings up both this and the idea of packaging as anti-composting, and I think that maps quite well onto the kind of conservation Kingsnorth and Leithart take issue with as it regards the West, viz. packaging-conservation, versus the kind of conservation I’m proposing in this essay, viz. composting-conservation. One is quite unnatural; the other is precisely nature.

The first law of thermodynamics states that energy can be converted from one form into another via heat, work, and processes, but it cannot be created or destroyed. Energy is conserved across forms, but it doesn’t disappear.

Hadden Turner writes a beautiful reflection on how, in nature, there always seems to be an abundance of life right at the site of death. It is a wonderful complement to the present essay and I commend it to your reading.

Storing the nutrients. Yaaaaa. And the seeds! They don't go in the compost pile. They go somewhere else. Historically, monasteries (Christian and other religions) stored the seeds. SubStack is storing e-seeds of all kinds right now.

What a breath of fresh air. Most Christians (and many who see Christianity as simply part of their western heritage) are racing to resuscitate the west more broadly and the US specifically. Others are convinced that the final judgement is going to be triggered by this fall. Some fight to save the country while chastising Christians that Jesus isn’t going to save them from the long March into communism. I am trying to reevaluate what the role of a Christian is in a constitutional republic that is largely secular. Your article is honest and hopeful in a way I don’t see much these days. Sorry if I rambled a bit, I am very thankful you showed up in my feed here on Substack.