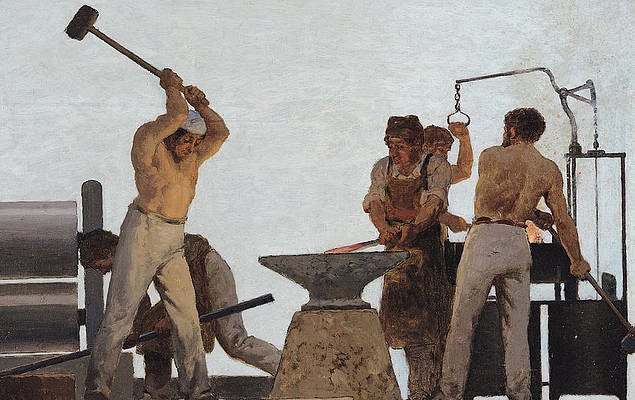

In the United States, today is National Blue Collar Day. Yes it has its own day, which probably doesn’t mean too much considering practically everything from cream puffs to drinking straws get to take up real estate on the American calendar and with the exception of federally recognized holidays, they all get trumped by work and sports anyway. Nevertheless, I happen to be of the opinion that this particular commemoration is a worthy one and since I call myself The Blue Scholar, I felt I couldn’t let the day pass without acknowledging this cultural high feast day.

I’ve had an uptick in followers recently—there are just shy of 600 of you now who say, “Yeah, sure, send me an email every once in a while,” which is wild to me—so this may be the first newsletter you’ve received from me. If that is the case: hello! On this occasion of my country ostensibly remembering the value of manual labor, I’d like to do three things:

Share with you a couple of essays on blue collar work written by others that have been meaningful to me,

Point you to some of my own essays from my career manually laboring,

And finally, share with you a poem written by Robert Stewart that I think nicely captures the blue collar experience, which will likely involve a brief commentary.

Essays from others

Matthew Crawford

I give pride of place to none other than

and his Substack, . If you’ve known me for longer than 15 minutes, there’s a good chance you’ve heard me say something about work and it was phenomenally intelligent-sounding. In that case, I was probably quoting Matt Crawford. He has done more to help shape my understanding of manual labor than any other single individual, so I’d like to point first to his corpus. Short of simply recommending you read everything he has written or will write, I suggest reading this piece of his:Shop Class as Soulcraft: The Case for the Manual Trades — this is an essay adapted from his book of the same title and really gives you a sense of how expansive his thought is. He focuses on manual labor as a means by which individual agency is formed and deployed in the world, a means which we desperately need in our present moment considering it’s making The Matrix look more like a documentary with each passing day.

Matt Crawford is a political philosopher by training, an electrician and mechanic by trade, and (apparently) a curious geek by disposition, so he’s able to weave numerous threads from multiple domains and disciplines into a convincing swatch of handsome herringbone (I’m learning to knit right now and I just learned to stitch a herringbone pattern and boy is it complicated, so Mr. Crawford, if you read this, that was a compliment).

Additionally, subscribe to his Substack. If you have to choose between paid subscription to mine or his, make it his. I’m that serious about this. He doesn’t only write about manual labor. He doesn’t even mainly write about manual labor. Really, his project is human agency and that which either cultivates or else denigrates it. 15/10 would recommend.

Elle Griffin

A number of months back I published my own essay on blue collar work on Substack which got a fair bit of traction and put me in contact with a grip of new people. Elle was one of them.

writes Substack and her husband, Garrett Griffin, is in the refractory industry. For those that don’t know, refractories are the materials that line the kilns and machines that make the materials that we used to make other structures. So he makes the things (refractories) that make the things (kilns, furnaces, reactors) that make the things (iron, steel, ceramic) that we use to make things (buildings, other various physical infrastructures, household items). What a badass.Elle has done her husband and everyone who manually labors to earn their bread a real solid by writing this wonderful piece on blue collar work, which I commend to your reading:

My own essays

Resonant with what Elle did in her essay, I have also written a piece on why blue collar work is awesome and why one ought to consider it as a career path. Or, if the time for fruitfully laboring with their bodies is behind them, then perhaps folks will point their children and others to a career in wrench-turning. If they need convincing that they should do this, they should read Matt Crawford’s essay linked above, and then Elle’s, and then this one:

A Career of Choice

Well hello! If this is the first newsletter you’re receiving from me: thank you so much for subscribing. I hope you won’t be sorely disappointed! This is a follow-up to my previous post in which I discuss how plumbing was an unexpected career for me and tell the story of how I ended up being a good old fashioned wrench-turner. I’d encourage you to go bac…

Now I’ll guess that someone read these essays and said, “Eureka! A career in the trades is just the one I’ve been looking for, but gee mister, how do I start?” I assume this is a common reaction, so I wrote a next-step piece to give some practical guidance and consideration:

A Practical Guide to Entering the Trades

I’ve told the story of how I ended up becoming a plumber, and I’ve attempted to make a case for trade work as a choice career that goes beyond simply listing off the available jobs and telling you that you’ll make good money (which are both true! But there’s so,

And then, more recently I wrote a piece on the role that language plays in the pursuit of mastery, a role that is just as large in the trades as anywhere else. I include it here mainly because I want to show that trade work isn’t all grunting: articulate use of language is a crucial aspect of acquiring competence as a plumber or a welder or a millwright or a machinist. I also hope that those who employ manual laborers and who depend on those laborers doing their work competently will allow what I call “yard talk” to occur:

In Defense of Yard Talk

A Morning at the Shop It's 6:46 AM and I still have a nugget of sleep cemented to my left lid. My driver's-side door greets my ears with its customary screech when I exit the dark cab and hop down to solid ground. As I cross the gravel and walk through the cement floored warehouse, I stop just short of me…

A poem

What is a C-class holiday without a poem, amirite? But unlike the holiday, this poem is A Grade. Poet and essayist Robert Stewart, son and grandson of plumbers, worked in his early summers as a plumber’s apprentice and learned the trade from the inside. His time as a laborer had such a profound effect on him that his collection of poems published in 1988 was called Plumbers and contained three sections, the middle of which has thirteen poems specifically about plumbing. It is from this collection that I share with you a short piece that anyone who has worn there body out by physical toil can relate to.

BOSS TOLD ME by Robert Stewart

shake hands with that shovel dig manholes straight and clean take gloves off patching sewers while rubbers and corn flow between my legs, boss told me elbows and assholes are all he wants to see, water bugs covering the inside of manholes like strange moving vinyl boss said, don't let them get on ya, boss'd cement your feet if you didn't keep movin, tell you he was twice your age and twice as good blow his nose on the ground during lunch, told me my back was all he was payin for, take good care of it.

Effort. Accuracy. Filth. Technique. Expectations. Pressure. Earnings. Care.

All of this and more is wrapped up in these few lines. And these—at least these—sketch an image of what it means to be a blue collar worker. Our labor in the physical world, the effort we exert and the accuracy with which we exert it, enduring filth often not of our own making, picking up the tricks of a given trade and meeting the demands of bosses and customers and coworkers, sitting under the sometimes crushing weight of deadlines and the even heavier weight of human need, all to make a living while we do the work that makes life livable for our families and neighbors and communities.

To all who shake hands with shovels, who drop dimes and wipe joints and measure twice to cut once and with dirty hands earn clean money: your labor is not in vain. Labor on.

Great stuff right there! Speaking for myself, doing manual labour has been way more rewarding than working in an office. Making things with your own hands (and getting paid to do it) gives you a whole different sense of achievement.

thank you for your great work on substack!