Hello, all!

I’ve had a big jump in subscribers following my essay, A Nightmare Dressed Like a Daydream. If this is the first email you’re receiving from me, then a very warm, hearty welcome to you! I’m grateful you took the time to read it and I’m thankful you’ve chosen to stick around. This newsletter is a departure from the previous in that I am doing less philosophizing and more reflecting (which aren’t categorically separate activities, but you’ll see what I mean shortly).

I hope you enjoy, and this (like all my work at the time of writing) is free, so feel free to share.

-Nate

I’ve said every year for the last four or five years, “This is the year that I start cultivating an appreciation for poetry.”

The lies we tell ourselves.

Not that I don’t appreciate poetry — the command of language, the turn of phrase, the rhythm and cadence, the economy of words, the ability to play with shades of meaning — it’s that I haven’t learned how to properly savor it. I heard it said once, “Never learn to appreciate wine because then you’ll only want the expensive stuff.” Right now I’m as happy with a $10 as a $100 bottle, if I’m honest with you, and that’s after a couple wine tastings and spending time with sommeliers. I’ve told the story before about my friend sharing his bottles of Chartreuse with me, and coaching me through tasting the flavor notes.

As if by magic, my tongue could now detect honey in the sweetness weaving through the floral notes. Sensory data, already present but invisible until language was provided to identify it, was now available for my enjoyment. As Crawford puts it, "[my] own experience [was] altered in conversation" (pg. 62).

As it was with Chartreuse, so it will need to be with me and poetry.

That said, I’ve discovered to my great delight that “blue collar poetry” is a thing. It exists! Is it a $10 bottle of wine? Couldn’t tell you. But by golly, it’s there and I’m gonna drink it.

Last year I stumbled across a small volume of poems by Robert Stewart. One might think that craft-related poetry would largely revolve around the artistic trades — woodworking, poetry, sculpture, painting — and one would likely be correct. Poetry circling the hubs of nature and agriculture is a fairly known genre as well, for which the Transcendentalists and Wendell Berry may need to be thanked. But Stewart did not write about flowers or farms, he did not wax eloquent on the idiosyncrasies of wood grain or the delicate stroke of a brush.

Mr. Stewart’s topic of choice was plumbing.

He wrote about other topics as well, but Stewart’s first volume of poems, the small one I encountered last year, is simply entitled Plumbers. However it was that I was expecting to learn to love poetry, discovering stanzas about soldering and sewers wasn’t it. But I thank God that this is His chosen means of grace.

After my eureka moment with Stewart I learned of Philip Levine and B.H. Fairchild and Jesse Bertron. And it is Bertron that brings me to the meat of today’s newsletter.

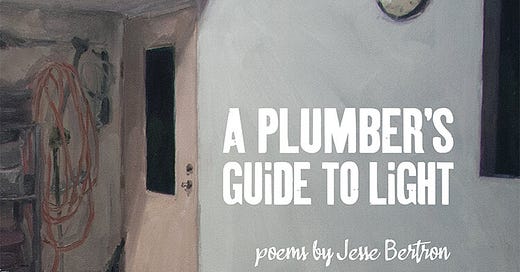

A Plumber’s Guide to Light

Jesse Bertron, at the time that this volume was published in 2021, was a plumber’s apprentice in Austin, Texas, USA. By this point he may very well be a journeyman plumber, a feat that requires 8,000 hours of training and experience across four years. In addition to being a drain surgeon, add the unique distinction of holding an MFA in Poetry from Vanderbilt University.

This less than fifty page book contains fifteen poems, and they are — remember what I said about my capacity for savoring poetry — divine. Take that for whatever it’s worth.

Bertron, with deftly chosen words, has produced a small body of work that somehow captures precisely what it feels like to be an apprentice plumber. If you’re new here, you may not yet know that I am a plumber by trade. Hence my joy at discovering Robert Stewart’s Plumbers and my affinity for Bertron’s poems.

I see myself wedged under a vanity in his eponymous piece. I know of what he speaks when he tells of the winter dark and summer’s soft evening light in “Working Late”, and the way one comes to know their coworkers in a more full, more human way when one continues to labor while the rest of the working world punches out and commutes home. In “Dear Jacob” he half roasts, half praises a fellow plumber by that name, apologizing for how he would prattle on about his “astonishing capacity for slop” (which he defines in another poem, “Slop”, as the measure you’re allowed to fall short of perfection in your work) but then lauding him for his uncommon kindness and his devotion to his wife. I cannot help but identify my own handful of Jacobs that I’ve turned wrenches with over the years. From dicks and vulvas scrawled on jobsite port-o-potty walls to his blue collar, alcoholic father that, despite Bertron’s pleas, wouldn’t change his ways until he one day did, these verses compose a billet-doux to plumbing and the life he’s lived in and around and through the trade.

There is a cast of characters we meet a number of times through Bertrons writing: Conner Finn, Tonio, Shorty. “Shorty” is the name of the first poem in the collection and it is from this piece that today’s newsletter takes its name. To anyone else, Shorty was likely indistinguishable from any Mexican day laborer you might see looking for work outside a Home Depot, but to Bertron, Shorty was an eternal refrain that never left his lips, the honey-sweet name of his teacher in the trade, the man to whom he would daily bring “bouquets of wrenches”. Whatever else Shorty may have been, he was the object of Bertron’s love. And a damn good plumber.

And apparently Shorty couldn’t read. Or maybe it’s that, like me, he simply doesn’t have an affinity for poetry? Something like this is hinted at when Bertron writes,

Why does it feel like an insult, Shorty to tell the truth? You will never read this poem.

And it is just this that makes the poem so interesting. If you have read my work, you will know how much I love Matthew B. Crawford and his thought on manual work in the world. It might be right to say that Crawford is my Shorty (but not my shawty, that’s entirely different). He has written convincingly of tacit knowledge, embodied cognition, the intelligence of the laborer, and themes that underpin and grow from these ideas. Using Crawford’s ideas as my jumping off point, in another piece I invoke Hugh of St. Victor’s Didascalicon to connect this embodied knowledge to reading. I will quote myself at length to make my point.

As Hugh conceives of it, this instruction [of Wisdom] is primarily brought to a soul through the art of reading, but not reading as one with a disposition of familiarity with the subject. Rather, one must read as on foreign soil, as an exile, as on a journey: as a journeyman, we might say. …

… [A] journeyman…would quite literally journey hither and yon, seeking to increase his skills under the tutelage of a master. The master contained in his flesh years of hard-won tacit knowledge; he housed in his mind decades of technique and lessons learned at the feet of failure; from his mouth poured forth until-then-unarticulated proverbs (and, just as likely, vibrant expletives). … Implicit in wielding tools to order the material world are the intellectual and moral faculties that direct their use. In a word, the journeyman seeks the master’s wisdom, made intelligible not through a book but through the master’s body.

And Bertron, with far fewer words filled with immense love, arrives at the same conclusion. Shorty may or may not be able to read, but he is a teacher and his body is a text. He writes, “I think now about school, all the school/I’ve been to—many years!—with Shorty sitting/on a five-gallon bucket with a toothpick/watching me. Sometimes talking. Watching me/flail beneath this hall bath lav, saying, that’s okay,/mijo, that’s okay each time I curse” — another wildly relatable line for this plumber — “and then/finally, taking the channel locks, and doing it right/so I could see.”

You may have guessed by this point where this is all leading, but allow me to unravel the skein a loop or two more.

In the trades, there is much that goes unspoken. Some of the best tradesmen I know are, frankly, illiterate. Not illiterate because unintelligent, but illiterate because of life’s circumstances. Despite their inability to read well or write goodly, they are capable, with a flick of their eyes and hard-won swiftness of thought, of a mental calculus that would make your head spin. Offsets and grades and pitches and angles and lengths and configurations and dimensions. They don’t even have to do the math anymore. Like a master artist, they just feel it. It’s a trained sense of what ought to be, and then their hands bring it into the world. They’d be quite unable to explain in articulated detail what it is that they’ve done, but that doesn’t matter. It is done.

Where words fail, the body speaks eloquently.

Bertron finishes, “Teachers used to sit with me./Together we would study some third thing./Shorty wears a silver bracelet/that shines like a lamp/and underneath it is the hand I read.”

Underneath it is the hand I read.

I have had the great fortune of reading many texts. Many books. Many Shortys. Jesse Bertron, the plumber poet, has done us the great service of honoring both in this wonderful, short collection of poems. I commend them to your reading. You can find Mr. Bertron’s book here1.

I get no percentage of any sale. This is not a paid advertisement. I love this book and hope you will too.

A thing I do from time to time is sit at the counter in a Waffle House and watch the short-order cooks. They hear orders, without writing anything down, and move constantly, not quickly, as you might imagine, but with measured efficiency, doing a few things at once, rarely messing up. No wasted effort or motion. It's what we call, "poetry in motion," a cliche, but a useful one.

In the popular imagination, and the imagination of many poets, Waffle House is as far from poetry as can be. Yet, those who know, or bother to observe, can see poetry in plumbing or short-order cooking. A skilled mechanic hears music in the car engine he can identify by make and model without seeing it. A carpenter can wax poetic about well-made kitchen cabinets and scoff at overpriced, under-quality work. I have heard that there are computer programmers who write code with a degree of elegance not necessary to get the job done, but do it anyway because of pride in their craft.

The connection between the trades and poetry is craft, the skill in making a thing. Craft isn't romantic; it involves skilled work, which takes time to learn, and time to use, much longer than jotting down a thought, breaking it into short lines with arbitrary punctuation and capitalization, and posting it to Instagram.

I'm turning 65 this year, and have written poetry since my teens, but I was too invested in the romantic mythology of inspiration to bother much with craft. My facility with language was enough to dazzle my small readership of family and friends, but little I've written so far is likely to outlive me. So now, with whatever time I'm granted, I'm taking craft more seriously, both in what I read and what I attempt to write. I can find inspiration from plumbers as much as poets. A plumbers' materials are pipes, joints and whatever else plumbers work on, while his tools are wrenches and so on; a poet's materials are words, his tools are metaphor, rhythm, irony, etc. It's takes as much skill and dedication to install a sink, sew a quilt or weave a basket as it does to write a poem. Anyone who pays attention can admire the work of all.

Thanks for the introduction to Jesse Bertran! I look forward to reading his work.

I'm glad you discovered Philip Levine. He's one of my favorite poets, and I was fortunate to get to spend time with him on a couple of occasions back in the day, so I can also report that he was a great human being as well. For anyone who's curious about his writing, here's a short poem.

Making it Work

by Philip Levine

3-foot blue cannisters of nitro

along a conveyor belt, slow fish

speaking the language of silence.

On the roof, I in my respirator

patching the asbestos gas lines

as big around as the thick waist

of an oak tree. “These here are

the veins of the place, stuff

inside’s the blood.” We work in rain,

heat, snow, sleet. First warm

spring winds up from Ohio, I

pause at the top of the ladder

to take in the wide world reaching

downriver and beyond. Sunlight

dumped on standing and moving

lines of freight cars, new fields

of bright weeds blowing, scoured

valleys, false mountains of coke

and slag. At the ends of sight

a rolling mass of clouds as dark

as money brings the weather in.